Introduction

Experts and clinicians, when asked about the impacts of social media on mental health, often highlight the opportunities provided by online spaces specifically for LGBTQ+ youth1. This research brief explores the current literature about the benefits online spaces confer and the risks of those spaces for young people who identify with a sexual and/or gender minority group, including how these youth find support and community, navigate risks, and explore their identities online.

As much discussion on social media in particular focuses on mental health effects, it is important to recognize that LGBTQ+ youth may be more likely to struggle with mental health concerns like depression and anxiety (CDC, 2024), and often face barriers in accessing care which appropriately meets their needs (Choi et al., 2023). This context is critical for understanding how LGBTQ+ youth navigate online spaces.

Within this framework, this research brief will seek to set the stage with the latest research on the state of mental health of LGBTQ+ youth, followed by an exploration of:

- Which experiences on the internet, and social media more specifically, benefit LGBTQ+ youth?

- Which experiences on the internet, and social media more specifically, increase the risks of harm for LGBT+ youth?

Given that the landscape of online spaces has changed significantly in recent years, in order to best reflect the current online environment, this research brief will primarily evaluate literature from the past five years, 2019-2024.

Mental Health Experiences of LGBTQ+ Youth

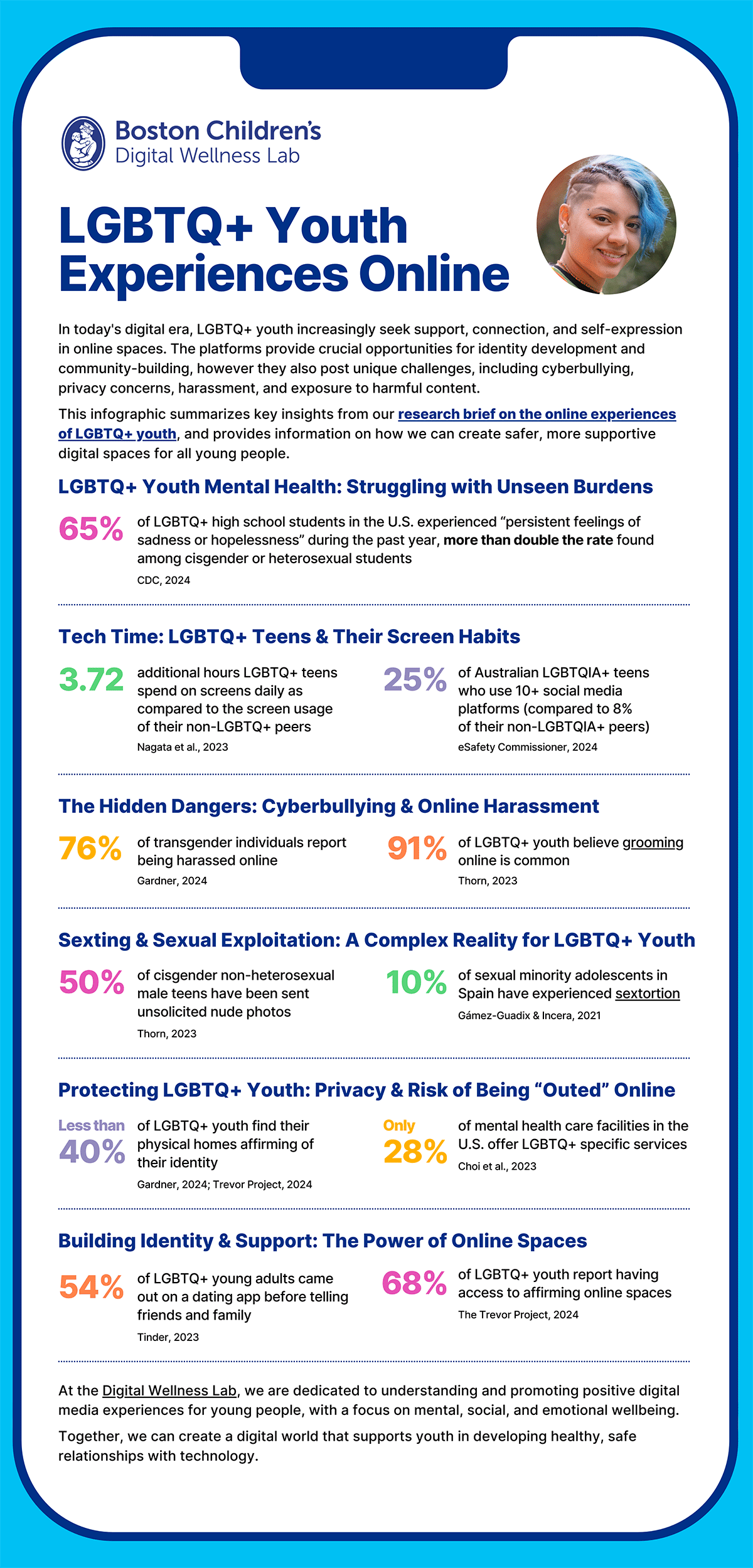

Young people in the LGBTQ+ community have nuanced experiences and unique considerations for their mental, emotional, and social wellbeing. Overall, teens and young adults who identify as LGBTQ+ report more mental health challenges than their cisgender and heterosexual peers. For example, the Trevor Project’s 2023 National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People (ages 13-24) found that 67% of respondents reported symptoms of anxiety and 54% reported symptoms of depression (The Trevor Project, 2023). The most recently available Youth Risk Behavior Survey data in the United States found that 65% of LGBTQ+ high school students experienced “persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness” during the past year, more than double the rate found among cisgender or heterosexual students (CDC, 2024). LGBTQ+ young people, especially younger adolescents, are also significantly more likely to express suicidal ideation than their cisgender and heterosexual peers (e.g. Miranda-Mendizabal et al., 2017; Ream, 2019).

Unfortunately, unique barriers also exist for LGBTQ+ youth seeking access to mental health care. While 84% of young people identifying as LGBTQ+ reported a desire to engage with a mental health counselor over the past year, 50% of those youth did not receive counseling services (The Trevor Project, 2024). Geographic location amplifies the challenge. LGBTQ+ youth in the Northeastern United States received access to mental health care (56%) more often than their Southern peers (45%) (The Trevor Project, 2024). One barrier to accessing care may be a general lack of identity-focused practice: in 2020, only 28% of mental health care facilities in the US offered LGBTQ+-specific services, with coastal states having higher rates of specific care programs than rural areas (Choi et al., 2023). Additionally, many young people noted feelings of fear around talking to someone about their mental health, and almost half of gender-questioning youth did not want to get permission from a parent or caregiver to speak to a counselor (The Trevor Project, 2024; Zullo et al., 2021). This latter finding is particularly concerning, as acceptance from a parent is associated with a significant decrease in past-year suicide attempt (Green et al., 2021). Addressing barriers to healthcare for LGBTQ+ young people is critical, as access to mental health and/or gender-affirming care can significantly lower suicidal ideation and attempts (Tordoff et al., 2022; The Trevor Project, 2024).

Media Use Habits of LGBTQ+ Youth

While a significant proportion of young people overall are engaged users of media, LGBTQ+ youth may be more likely to be heavy users both in time spent and spaces visited. One recent analysis of a large longitudinal data set of adolescent screen use in the United States found that identifying with a sexual minority resulted in an average 3.72 hours of additional daily screen time (Nagata et al., 2023). Recent research in the United States and Australia has found that LGBTQ+ young people are more likely to use a greater number of mobile applications and social media platforms, and to hold multiple accounts within a platform, as compared to their cisgender and heterosexual peers (eSafety Commissioner, 2024; Madden et al., 20204; Thorn, 2023). For example, while only 8% of the Australian teen population surveyed used over 10 social media platforms, 25% of LGBTQIA+ teens said the same (eSafety Commissioner, 2024).

Research evaluating the media habits of LGBTQ+ youth has often described their online experiences as a “double edged sword,” including both more positive and more negative experiences for these youth compared to their cisgender and heterosexual peers (e.g. Fisher et al., 2024; Madden et al., 2024). A majority of LGBTQ+ youth describe social media as both positive (96%) and negative (88%) for their mental health (The Trevor Project, 2021).

In the United States, sexual minority youth are much more likely than others to use online resources for sexual exploration and sexual health information (e.g. Delmonaco & Haimson, 2022; Mitchell et al., 2014; Robb & Mann, 2023). While similar patterns of use are found in other countries primarily considered “Western” and developed (e.g. Bradlow et al., 2017; eSafety Commissioner, 2024), far less is known about the online behaviors and experiences of LGBTQ+ youth in areas where queer relationships and gender minority expression are criminalized or face high levels of discrimination, despite the fact that these factors may drive LGBTQ+ people to seek partners online rather than in-person at higher rates (e.g. Thomann et al., 2020).

In the United States, intersectional analyses to compare the media use habits of LGBTQ+ youth who also identify as a racial minority are sparse, though some research has sought to explore the online experiences of multiply-marginalized youth (see: Cho, 2018; Lucero, 2017; Schmitz et al., 2022). As research continues to highlight the unique experiences of LGBTQ+ youth online, it is important to continue developing a context to evaluate how LGBTQ+ youth navigate online spaces with relation to all facets of their identity (i.e. gender, race, sexuality, socioeconomic status), rather than assuming a ubiquitous experience for all gender and sexual minorities independent of other factors.

Positive Online Experiences – Support and Identity Development

A substantial body of research has explored how LGBTQ+ youth navigate social media to support their identity development, find affinity spaces online, and form connections with peers. In fact, in his 2023 Advisory on Social Media and Youth Mental Health, the U.S. Surgeon General called attention to research that suggests that marginalized youth, including sexual and gender minorities, may uniquely benefit from the connection opportunities provided by social media (Office of the U.S. Surgeon General, 2023).

Exploring LGBTQ+ Identity Online

A recent evaluation of sexual identity milestones (e.g., first attraction, self-identification as sexual minority identity) found that today’s LGBTQ+ youth begin to notice attraction in early adolescence, then self-identify and engage in sexual experiences as they enter later years of adolescence; in contrast, older generations were more likely to have engaged in same-sex behaviors before identifying as a sexual minority (Bishop et al., 2021; Hall et al., 2021). During the adolescent years, young people may use online spaces and resources to understand their feelings and develop their sense of identity. For some young people, especially during early adolescence, online spaces may be a safe place to explore and practice aspects of identity before “coming out” offline. This online information-seeking has been recognized as a common practice for LGBTQ+ young people during their identity formation and “coming out” process for over a decade (e.g. Craig & McInroy, 2014; Fox & Ralston, 2016; Gray, 2009).

Unfortunately, research has found that less than 40% of LGBTQ+ young people find their physical homes to be affirming of their identity (Gardner, 2024; The Trevor Project, 2024), and many young people who are discovering their sexuality may not have access to supportive offline communities or feel comfortable talking about their identity with trusted adults or friends. As a result, online spaces often serve as places where young people feel safer seeking information about and connection around their sexual and/or gender identities. In the United States, over half (54%) of LGBTQ+ young adults say they were out on a dating app before telling friends and family about their identity (Tinder, 2023).

Online fan spaces for connection and creation within pop culture have historically been places where LGBTQ+ teens and young adults find community and support while exploring their interests and sexual identity (see “Online Fan Spaces” in Young People’s Sense of Belonging Online). Recent work has explored how social gaming, and more specifically avatar creation, could also provide opportunities for trans and gender diverse youth to feel affirmed and explore different presentations of gender (McKenna et al., 2024; Morgan et al., 2020). For example, one adolescent described avatar creation and gameplay as a way to “test the waters of coming out to people online and see how they respond before doing it IRL [in real life]” (McKenna et al., 2024, pp. 38). While all adolescents are forming and testing out identities, sexual minority identities may feel riskier to present to friends, family, and the offline world as a whole. Online spaces such as social media platforms, forums, and video games, can provide an opportunity for identity development and self-discovery for LGBTQ+ youth who may not feel safe or comfortable first exploring these identities offline.

Online Support and Community

For teens self-identifying as LGBTQ+, social media in particular can be an outlet for finding others like themselves, providing hope, solace, and connection (Berger et al., 2022; Fish et al., 2020; Hopelab, 2024). While young people frequently have parasocial relationships with media characters, social media also allows for the formation of parasocial relationships with “influencers” and content creators. While there are some concerns about how parasocial relationships can be exploited to market products, there are also benefits to these relationships, as they can inspire a sense of connection (Lou, 2022; Lou & Kim, 2019; Woznicki et al., 2021). For LGBTQ+ youth, these relationships may hold particular importance: a recent report found that transgender people with stronger parasocial relationships also had higher levels of transgender pride and community connectedness (Hopelab, 2024). The visibility of trans content creators may help trans youth navigate challenges or feelings of isolation, while witnessing other trans people authentically and joyously living their lives.

While content creators with large followings may not deeply engage with their viewers, LGBTQ+ youth may be cultivating smaller supportive communities of peers who are navigating similar life experiences. LGBTQ+ youth are more likely than their cisgender and heterosexual peers to join a group or online community, including group chats with online friends or online groups acting as an extension of an in-person group, like a club or support group (Charmaraman et al., 2021). In a survey of LGBTQ+ youth, 68% reported that they have access to affirming spaces online, 14 percentage points higher than the second most-frequently cited space, which was school (The Trevor Project, 2024). LGBTQ+ teenagers who reported that they have found social media to be a place of connection have explained that it allowed them to “make friends like me,” which can sometimes feel safer than trying to find other LGBTQ+ people offline (Fisher et al., 2024, p. 3). For some young people who may not yet feel comfortable sharing their sexual or gender identity with offline friends and family, online friends can seem better at providing emotional support (Ybarra et al., 2015).

Other factors, like the lack of visibility of offline support systems, may also play a role in the perceived value of online social support, with those in rural areas finding increased value in online spaces (Wagaman et al., 2020). This is supported by research exploring the experiences of LGBTQ+ youth who could not access in-person support during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Young people who identify as LGBTQ+ expressed a sense of loss about the lack of in-person safe spaces during the COVID-19 lockdowns, as well as a sense of gratitude for their online communities (e.g. Fish et al., 2020; Malmquist et al., 2023).

For some, the loss of in-person meeting places was associated with grief. One interviewee from Sweden specifically highlighted how queer culture has often revolved around in-person celebrations or events like Pride celebrations, which were curtailed during the pandemic lockdowns (Malmquist et al., 2023). Other young LGBTQ+ people, including those in rural areas, those who had limited or no familial support, and those where were not yet “out,” reported that they greatly appreciated the increased availability of online connections within the LGBTQ+community (e.g. Fish et al., 2020; Malmquist et al., 2023).

Heightened and Unique Risks

Cyberbullying and Indirect Violence

While there are risks involved with specific media behaviors or features of media platforms,for LGBTQ+ youth, these risks may be amplified or uniquely dangerous for this subgroup of youth. A systematic review of cyberbullying reported that LGBTQ+ young people were at increased risk for online harassment as compared to their cisgender and heterosexual peers (Abreu & Kenny, 2018). While nearly half (46%) of teens in the United States report having ever been victims of cyberbullying (Vogels, 2022), 76% of transgender individuals report being harassed online and 47% of LGBTQ+ individuals report having been cyberbullied within the last twelve months (Gardner, 2024). Over a third of American teenagers (36%, down from the previous year’s 47%) reported that online harassment led to offline harassment within the past year, and a third of teenagers (31%) reported viewing anti-LGBTQ+ content online including that LGBTQ+ individuals are grooming young people (ADL Center for Technology & Society, 2024).

For younger adolescents who may be exploring their identity or beginning the process of coming out, these experiences are unfortunately very common, with 54% of LGBTQ+ middle schoolers in the United States reporting being cyberbullied (The Trevor Project, 2021). These experiences can increase feelings of depression and suicidal ideation, two mental health concerns where LGBTQ+ teens and youth are already at heightened risk (Abreu & Kenny, 2018; CDC, 2024; Miranda-Mendizabal et al., 2017; Ream, 2019). Unfortunately, while online friendships can sometimes provide emotional support, research suggests those friendships do not incur protection from bullying or harassment, unlike in-person support (Ybarra et al., 2015). It is therefore important to continue to increase acceptance of LGBTQ+ adolescents and provide them with both offline and online support systems to decrease experiences of direct victimization.

While direct cyberbullying is an acute and personal risk, hateful and prejudiced rhetoric directed at their community can also affect LGBTQ+ youth online. While slightly over half of cis/heterosexual youth in the United States have encountered transphobic or homophobic comments online, over 75% of LGBTQ+ youth report the same (Madden et al., 2024). As LGBTQ+ youth are more likely to seek support and information online regarding their mental health (eSafety commissioner, 2024), it is critical that they can navigate online spaces and communities in ways that protect and support their mental health.

Sexting and Sexual Exploitation

While sexting is not uncommon for young people, LGBTQ+ youth often report higher levels of sending and receiving sexual messages. For example, one study found that LGBTQ+ youth in the United States were almost twice as likely to have shared nude images of themselves than their non-LGBTQ+ peers (Mori et al., 2022; Thorn, 2023). However, while sexting behaviors may incur additional risks for the participants, these activities may be seen as a more normalized practice among LGBTQ+ youth, who are more likely to be two-way sexters (both sending and receiving messages), using the opportunity to explore their own sexuality (Foody et al., 2021; Thorn, 2023).

While many LGBTQ+ youth may actively engage in these behaviors for expressive purposes, risky and exploitative online sexual experiences are unfortunately common for sexual minority youth.

In the United States, 91% of LGBTQ+ youth report that they believe that grooming online is at least somewhat common, and over 50% of cisgender non-heterosexual male teens have been sent nude photos they did not ask to receive, compared to 26% of their cisgender heterosexual male peers (Thorn, 2023). In Spain, almost 10% of sexual minority adolescents reported being victims of sextortion, which included sexual coercion and threats (Gamez-Guadix & Incera, 2021). Possibly due to the higher prevalence of victimization, more LGBTQ+ teens are having discussions about things like online sexual predators with their friends; interestingly, for many topics like sexting and sexual predators, LGBTQ+ teens were much more likely than their non-LGBTQ+ peers to turn to online only friends for discussion (Thorn, 2023), continuing to underscore the importance of online information and support-seeking behaviors of LGBTQ+ youth.

Privacy Concerns and Being “Outed”

Privacy concerns have also been explored within the context of queerness and identity formation; LGBTQ+ youth may manage privacy features differently from their peers depending on their comfort with sharing their identity with friends or family. For many platforms, there is a default expectation of publicness, such as the ability to easily and automatically add people from your phone contacts. While this may make creating an overlapping online/offline network easier for some, for queer youth who are still exploring their identity or who exist in unsupportive physical environments, this raises the risk of being unintentionally outed. LGBTQ+ early adolescents are less likely to report having family members as friends on social media, possibly because of this desire not to share their developing identity publicly online (Charmaraman et al., 2021).

Unfortunately, some youth have experienced unintentional outing to friends and family, attributing those experiences at least in part to the default publicness of platforms like Facebook. LGBTQ+ young adults described spaces like Facebook as having a high level of surveillance, where they feel unsure about what behaviors (e.g. liking a queer event page) others in their network can see (Cho, 2018).

In contrast, teens felt that the platform Tumblr was a space where they could be more expressive, as there was less focus on networking with others known offline and more control over what was seen by whom (Cho, 2018). Although the structure of Tumblr has changed somewhat since this research, its anonymity still appeals to many LGBTQ+ users, and a significantly higher percentage of LGBTQ+ young people report using the platform (compared to their cisgender and heterosexual peers) to connect with people who share their experience and identity (e.g. eSafety Commissioner, 2024; Nelson et al., 2023; Robards et al., 2020). As of this writing, the welcome page of Tumblr proudly includes “it’s the gay people in your phone,” possibly referencing the site’s historical popularity for queer discourse (Tumblr, 2024). The popularity of a platform like Tumblr speaks to a need to more deeply understand the unique experiences of LGBTQ+ youth navigating the division between their private and public lives; assuming a default publicness as more safe may not be true for all adolescents and young adults.

Conclusion

While LGBTQ+ youth are using media in many of the same ways as their cisgender and heterosexual peers, they engage in online behaviors that highlight the importance of identity-building and connection within queer and/or LGBTQ+ communities and spaces. Importantly, LGBTQ+ youth are not a monolith; while this brief has introduced many of the positive and negative aspects of online engagement for LGBTQ+ youth, there is great variety in the online experiences of different individuals and intersectional identities.

While LGBTQ+ youth are using media in many of the same ways as their cisgender and heterosexual peers, they engage in online behaviors that highlight the importance of identity-building and connection within queer and/or LGBTQ+ communities and spaces. Importantly, LGBTQ+ youth are not a monolith; while this brief has introduced many of the positive and negative aspects of online engagement for LGBTQ+ youth, there is great variety in the online experiences of different individuals and intersectional identities.

Many existing publications focused on the experiences of adolescents online do not directly compare different minority sexual and gender orientations, instead evaluating the LGBTQ+ adolescent community as a whole. Research that does evaluate separate identity groups (e.g. Nelson et al., 2023; Thorn, 2023) has found a large degree of variation in experience.

It is critical to develop research with increased attention to how specific sexual and gender identities and intersectional identities experience their online environments. In order to best protect marginalized youth online, we must seek to understand their experiences, both positive and harmful, so that platforms can create spaces and features which meet the social needs of all adolescents while mitigating risks that are unique to sexual minority youth.

This research brief was written by Kaitlin Tiches, MLIS, Medical Librarian and Knowledge Manager at the Digital Wellness Lab. For more information, please email us.

- There are numerous abbreviations to refer to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, queer, two-spirit, and other sexual and gender minority communities. Language is constantly evolving so, to be as inclusive as possible, we are using the abbreviation “LGBTQ+” to refer to this community of youth. Further information about abbreviations and community definitions can be found at https://thecentercv.org/en/blog/the-guide-to-lgbtq-acronyms-is-it-lgbt-or-lgbtq-or-lgbtqia/ ↩︎